The Boat that Sank

the Sibelius opera that got away

‘I believe that music alone, that is to say absolute music, is in itself not enough. It arouses emotions alright and induces certain states of mind, but it always leaves something unsatisfied in the soul. One always asks, why this? Music is like a woman; it is only through man that she can give birth. That man is poetry. Music attains its fullest power only when it is motivated by poetic purpose. In other words when words and music combine.’

This is what Sibelius wrote in a letter to a potential librettist, the poet J.H. Erkko, in 1893. It reads like a slightly jumbled paraphrase of one of Richard Wagner’s central themes in the lengthy essay Oper und Drama (1852) which Sibelius for a while found inspirational.

Sibelius is not known for his operas, but his sole foray into the genre, The Maiden in the Tower (1896), has the distinction of being the first opera written by a Finn. Two years before this rarely produced one-act opera he planned an ambitious work based on some cantos from the Finnish epic Kalevala; although The Building of the Boat ran aground in the dry dock, the hull and some bits and pieces were salvaged, and the overture metamorphosed into the tone poem The Swan of Tuonela. Sibelius wrote more than 100 art songs and they make up about one fifth of his oeuvre. He also wrote incidental music for a dozen or so stage productions. All this in my opinion proves that he had it in him—he could have been an opera composer but circumstances and the musical climate weren’t in his favour. He could also have done with a first-class librettist, instead of a couple of plodding poets.

At the time of Johan Christian Julius Sibelius’s birth (8 December 1865) Finland was a musical backwater with not a single professional symphony orchestra, let alone a permanent opera company. Frederik Pacius, a Hamburg-born migrant based in Finland, composed a few operas with Swedish librettos, but he is most famous for composing the music for the Finnish national anthem (1848).

Finnish musicians and singers who wanted to reach a professional standard studied in Germany, Sweden or Russia and so the conductor and composer Martin Wegelius decided in 1862 to found the country’s first conservatory, where Sibelius studied. Eleven years later the theatre director Kaarlo Bergbom established the first professional Finnish-speaking theatre company and also staged operas translated into Finnish. Bergbom’s opera company was short-lived and it took until 1911 before another permanent ensemble was started by Aino Ackté, who was Richard Strauss’s favourite Salome. Ackté gave the first performances of many of Sibelius’s songs and he dedicated Luonnotar (1913), his unique fusion of tone poem and solo cantata, to her.

‘Janne’, as family and friends called him, spoke only Swedish as a child. He attended the first Finnish-language grammar school in Hämeenlinna, where music was an important part of the syllabus. His Finnish became fairly fluent, but it is evident from letters to his wife Aino that his grammar skills remained poor. Surely it is not irrelevant that only six out of Sibelius’s 100-plus songs for solo voice and piano have Finnish lyrics. There are more songs in German than Finnish, but the vast majority are inspired by poets writing in Swedish. Setting Swedish lyrics to music was always going to be easier for Sibelius, but he learned to deal with the inflections and the vowel sounds that are so different in Finnish and endeavoured to use texts from the Kalevala for a number of cantatas and choral settings. With age he probably became more comfortable with Finnish texts but the libretto of The Building of the Boat, which had to be in Finnish to qualify for a competition, was a major stumbling block, and in the end its weakness probably sank the project.

Richard Wagner’s influence on Sibelius’s early orchestral works is unmistakeable, despite the fact that in the 19th century there were few opportunities to hear his music in Finland. There wasn’t even a theatre with a stage or an orchestra pit large enough to mount a full-blown Wagner production. These limitations didn’t dampen the enthusiasm of keen Wagnerites, however, among them Martin Wegelius.

Teachers and students at the conservatory occasionally performed scenes from Wagner operas and the composer and conductor Robert Kajanus, who founded Finland’s first professional orchestra, featured the Siegfried Idyll and various overtures in his concerts. Sibelius’s first experience of Wagner’s operas came in September 1889 when he was studying in Berlin and saw Tannhäuser and Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. ‘In my innermost soul was such a strange mixture of admiration, disapproval and rejoicing,’ he informed Wegelius.

A year later Sibelius moved to Vienna where he took some lessons with Karl Goldmark, famous for his opera Die Königin von Saba, and Robert Fuchs, who taught many notable composers, among them Mahler, Zemlinsky and Enescu. Sibelius partied hard and lived beyond his means. He wrote to his fiancée Aino, who was a fluent Finnish speaker, that he was studying the Kalevala diligently. He would have struggled with the archaic Finnish, but was probably also trying to impress his bride-to-be.

The Kalevala was compiled in the 1830s by the physician and linguist Elias Lönnrot from ballads, incantations and poems he had heard in Karelia and the north-eastern (Kajaani) region of Finland. The definitive edition of the Kalevala is made up of 50 ‘runos’ or cantos that previously had been transmitted orally. Only a few of these poems would have been known by the wider public. Lönnrot constructed the overall narrative of this saga, made up the title and probably added quite a number of verses to link the various sections that he had gathered on his many field trips. The Kalevala made an immediate impact on the growing Finnish national consciousness.

The Finns were reasonably happy under the rule of Emperor Alexander I. He had driven out the Swedes in 1809 and made Finland an autonomous Grand Duchy with a modicum of self-government. The population and prosperity increased significantly. Administrative and judicial affairs continued to be conducted in Swedish for a long time, which led to tensions between Finnish and Swedish speakers. The Fennoman movement strove for language parity and in their view Karelian culture symbolized the essence of Finnishness. Sibelius sympathized with the Fennoman cause, but he remained loyal to his many Swedish-speaking friends and supporters as well.

‘The Kalevala strikes me as extraordinarily modern and to my ears is pure music, themes and variations,’ Sibelius wrote in a letter to Aino on 26 December 1890. Just like his friend Robert Kajanus before him, Sibelius decided to set the tragic tale of Kullervo to music. It is a story about child abuse, slavery, an unwitting incestuous relationship and suicide. ‘Wagner, eat your heart out!’, Sibelius must have thought when he was contemplating the material.

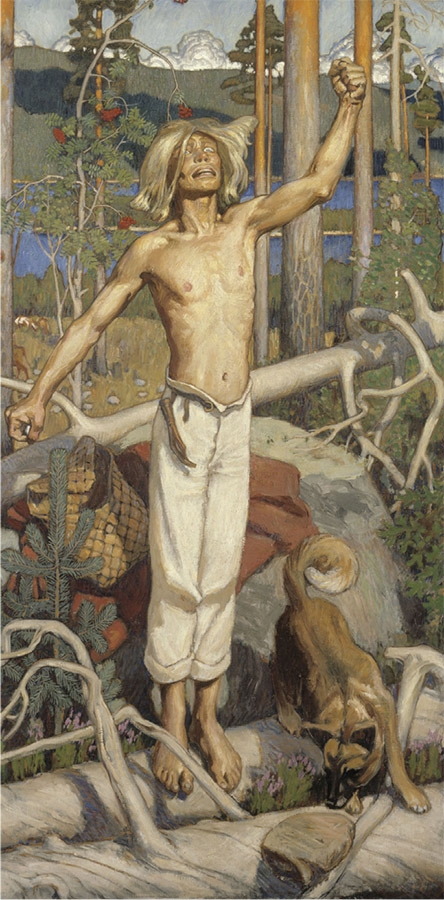

The troubled Kullervo meets, seduces and then ravishes a young woman, only to discover that she is his long-lost sister. She throws herself into a river and drowns. Kullervo deals with his inner demons by going to war against his uncle Untamo who maltreated him and sold him into slavery when he was young. Kullervo slaughters his uncle and his tribe. On his way home he passes the place where he sexually forced himself on his sister and, overcome by guilt, falls on his sword and dies.

Initially Sibelius set out to compose a symphony, but his Kalevala studies inspired him to introduce a choir, baritone and mezzo-soprano soloists to the Kullervo mix. The nine months in Vienna were, despite the partying, a productive period, but by the summer of 1891 Sibelius was back in Finland, where there came an opportunity to hear the old and legendary rune-singer Larin Paraske perform Karelian poetry. The typical trochaic tetrameter, the unusual inflections, prolonging and stressing the last syllable of a word, did not immediately impress Sibelius but were eventually absorbed into his choral symphony.

Brahms and Bruckner come to mind in the first movement of Kullervo, but by the time we move into the ‘Kullervo’s Youth’ movement, which has a Russian feel, interlaced with threads of folk song, it is clear that Sibelius has found his own voice. The male choir and soloists are introduced in the third movement—Sibelius had planned a mixed choir, but he thought that the women would be embarrassed to sing about, and listen to, the rousing music portraying Kullervo’s sexual intercourse with his sister. The initial time signature of 5/4 may seem odd but is common in Karelian folk music.

In general the music is more abstract than illustrative, but he does make war appear to be a cheerful business (as in the text) and under-emphasizes, or even leaves out, some of the drama. The choral parts are eloquent but have more in common with Gregorian chant than runic singing. I defy anyone to listen to the Sister’s lament and the final movement and not hear a future opera composer. Sibelius was 26 years old and Kullervo was his first major orchestral work. He would in later life, jokingly, refer to it as his first symphony.

The premiere, conducted by the composer on 28 April 1892 in Helsinki, was a great success. Many people immediately identified the tale of the anti-hero Kullervo as embodying Finland’s struggle to remain autonomous. The success of Kullervo demonstrated that epic Finnish themes not only worked in literature, but could also be effective in music. The critics were initially positive but for some curious reason they became disparaging when Sibelius conducted some additional concerts the following year. Understandably Sibelius was disappointed and withdrew Kullervo. It was at this point that he found solace in reading Wagner’s essay Oper und Drama, and concluded that ‘music without words cannot satisfy mankind’.

Sibelius started to feel confident enough to try his hand at composing an opera. He was striving for a synthesis of words and music, and his ambition was to continue where Wagner had left off. The Kalevala seemed as good a source as the Nibelungenlied, and Väinämöinen, the powerful seer and master musician, was potentially a more interesting character than Siegfried. There was another reason why Sibelius wanted to work within a nationalist framework: it gave him a chance to compete for a lucrative opera prize that had been announced by the Finnish Literature Society. The stipulations were that the libretto had to be in Finnish, based on a historical or mythological text.

Sibelius chose two cantos from the Kalevala to form the basis of the libretto for Veneen luominen (‘The Building of the Boat’) and a poet, J.H. Erkko, with a complete lack of theatrical experience who produced a text that, when Sibelius showed it to Kaarlo Bergbom, was deemed by the theatre director to be too lyrical and insufficiently dramatic.

He put the opera on hold while he was distracted by a commission to write incidental music for eight tableaux depicting the history of Karelia. Despite the nationalistic undertones, these kind of works managed to slip beneath the radar of the Tsarist censors. The Karelia Suite was and remains one of his most popular orchestral works.

In the summer of 1894 Sibelius revived his opera project, having dropped his librettist, and sought inspiration in Bayreuth: ‘Heard Parsifal. Nothing in the world has ever made so overwhelming an impression on me. All my innermost heartstrings throbbed,’ he wrote gushingly to Aino. The following day’s performance of Lohengrin brought him down to earth with a thud: ‘It did not have the impact on me that I had expected. I can’t help finding it old-fashioned and full of theatrical effects […] I thought of my own opera and went around humming bits of it. I am the only one who believes in this opera of mine.’

He headed for Munich, where the opera season was about to start, his letters revealing extreme mood changes and suddenly including a plot outline for another opera idea altogether, in verismo style. Together with his brother-in-law, the conductor Armas Järnefelt, and his wife, a talented singer, Sibelius returned to Bayreuth, where a superb performance of Tristan und Isolde bowled him over and where it probably started to dawn on him that he didn’t yet have the skills to continue where Wagner had left off. A production of his favourite Die Meistersinger was the straw that broke the camel’s back. In a letter to Aino on August 22 he wrote: ‘I was very taken with Meistersinger but, strange to say, I am no longer a Wagnerite. Nothing I can do about that—I must be led by my inner voices.’ Those voices told him to abandon ship. The Building of the Boat was dead in the water. Some of the themes and material from the opera probably ended up in the tone poem The Wood-Nymph. The opera’s overture with its mournful cor anglais solo became, as noted above, The Swan of Tuonela. It is a perfect paraphrase in A minor of the Lohengrin prelude.

Two years after the abandonment of The Building of the Boat Sibelius received a commission to write a piece for the benefit of a lottery in aid of the Philharmonic Society Orchestra. He chose to return to the genre that he had failed to master previously and produced Jungfrun i tornet (‘The Maiden in the Tower’), a one-act opera lasting 35 minutes. The ineffectual Swedish libretto by the novelist and poet Rafael Hertzberg hardly bears scrutiny. The music on the other hand is colourful and the Italianate intermezzo (Mascagni?), the maiden’s prayer (Verdi?) and the lovers’ duet are powerful—there are traces of Wagner everywhere but the Sibelian character is unmistakeable.

Sibelius conducted the premiere of The Maiden in the Tower in November 1896, but after a couple of performances withdrew the opera and it was never staged again during his lifetime. In 1911 Aino Ackté tried to persuade him to revive the piece but to no avail. She also sent him a libretto of Juhani Aho’s popular novel Juha. After considering it for two years (!) Sibelius once more declined—subsequently Juha was successfully set to music by both Aarre Merikanto (1922) and Leevi Madetoja (1935). He also considered Blauer Dunst (‘Blue Smoke’) by Adolf Paul, a commedia dell’arte play with a Spanish setting; but it is hard to imagine Sibelius composing an opera buffa, and the idea was dropped.

In his mind Sibelius probably never gave up on opera but the work on his symphonies and tone poems started to take up too much of his energy and time. He never lost his interest in the stage and wrote incidental music for 11 plays. The musicologist and composer Erkki Salmenhaara accused Sibelius of ‘squandering musical ideas’ on stage plays, but this verdict seems extremely harsh when you listen to some of the marvellous incidental music composed for Kuolema (‘Death’, 1903), Pelléas et Mélisande (1905), Svanevit (‘Swanwhite’, 1908), Belsazars Gästabud (‘Belshazzar’s Feast’, 1906) and Stormen (‘The Tempest’, 1925). Sibelius learned a great deal from his ‘Wagner period’ and one could argue that he, like Mahler, brought the influence and his experience of opera to bear on many of his orchestral compositions.

Could it be that Sibelius in the end took heed of his most trustworthy friend and supporter Axel Carpelan’s advice? Carpelan wrote in a letter to Sibelius in June 1900: ‘Operas are often just expensive playthings for the semi- or unmusical masses. What a small people like ours needs are not operas, not even national operas, but primarily soulful songs for one voice and mixed choirs (performances by male choirs are a disaster!).’ The truth is that in 1894, while still in Bayreuth, Sibelius had already realized that his true strengths were in a different genre. He wrote home to his long-suffering wife on August 19: ‘I am really a tone painter and poet. Liszt’s view of music is the one to which I am closest. Hence my interest in the symphonic poem.’