Bruckner

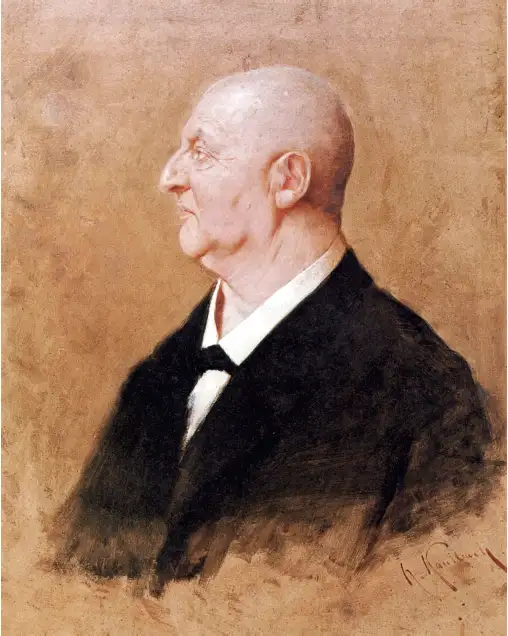

Labelled a “bumpkin” by Brahms, who detested his symphonies, Bruckner is now regarded as one of the greatest symphonists of the Romantic era. As four Australian orchestras prepare to perform his music on the bicentenary of his birth, Albert Ehrnrooth traces Bruckner’s career, along with his obsessions and oddities.

SYMPHONIC BOA- CONSTRICTORS?

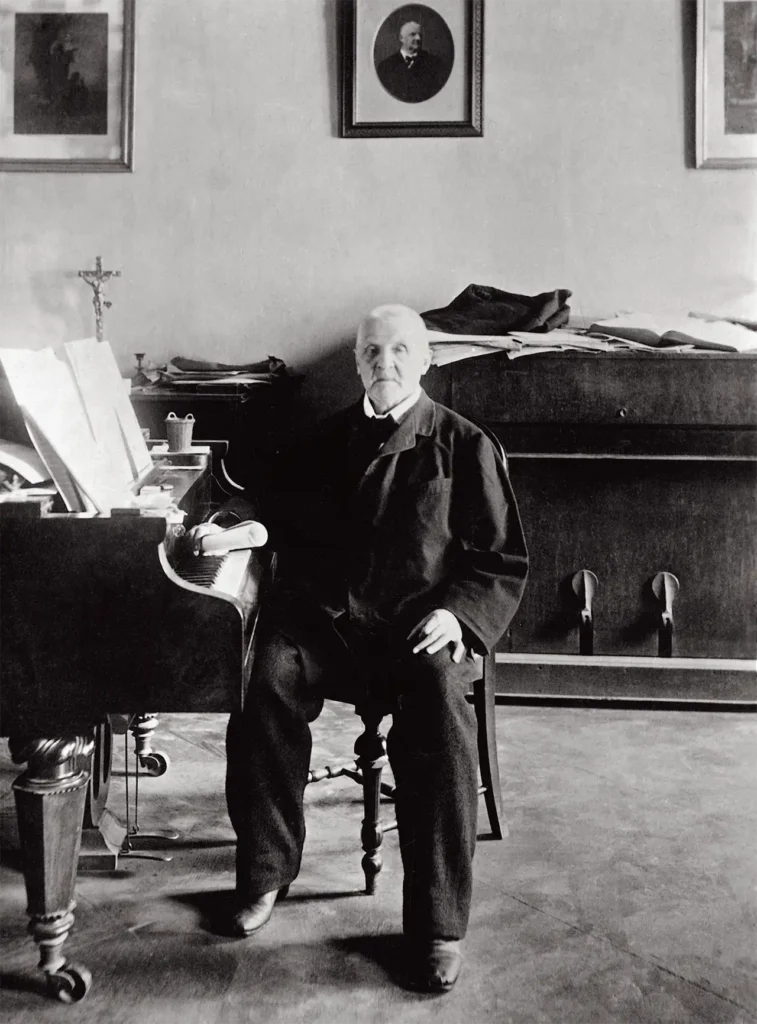

Anton Bruckner wrote in his will that he wanted to be a “Leiche erster Klasse” – a first-class corpse. He had a penchant for hanging around cemeteries and witnessing executions, and was rumoured to have kissed the skulls of two of his favourite composers, Beethoven and Schubert. On top of his ghoulish obsession, he suffered from a compulsive urge to count his actions and objects, from his daily prayers to the leaves on a tree to the sequins on his sister’s dress. At times, his obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) was off the scale. Even more disturbing were his marriage proposals to teenaged girls – the last one when he was 56. (As a devout Catholic, it was important to him that his prospective young bride was a virgin.) Time and again, he was rejected. His terrible dress sense would have been an instant put off; he wore oversized clothes (he hated sweating) peasant shoes

and a floppy hat. In swanky Vienna, he was treated like a country bumpkin.

During his tenure as Chief Conductor of the Queensland Symphony Orchestra, Johannes Fritzsch conducted five of Bruckner’s symphonies. In August, he returns to the QSO, where he is currently Principal Guest Conductor, to lead two performances of Bruckner’s unfinished swan song, his Symphony No. 9. “Bruckner was a petty person; very narrow-minded in day-to-day business and very strange in his relationships with other human beings, including women. All those shortcomings in his life you find in his music,” says Fritzsch.

“There’s a huge and unbelievable deepfelt longing for something else. That is extremely strong in the Ninth Symphony. You look at the second theme in the first movement, that is all longing for something. You might say that it is longing for some spiritual aspect, but there is so much human being in it. It can break your heart when you listen to it. This poor man poured out his heart in the score.”

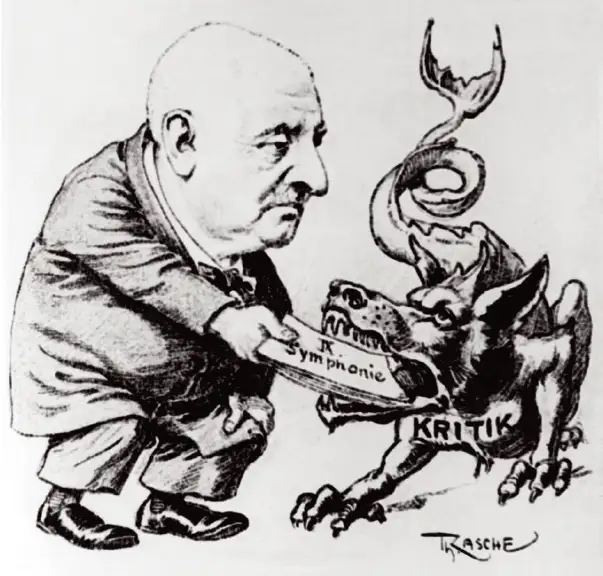

While Bruckner’s choral works were generally well received during his lifetime, conductors and music critics, as well as his friends, often struggled to comprehend his symphonic writing. The conductor Hans von Bülow commented that he was “half genius, half simpleton”, while Brahms accused him of composing “symphonic boa-constrictors”.

Bruckner only tasted international success as a composer at the age of 60 when his Seventh Symphony was premiered to great acclaim by Arthur Nikisch in Leipzig, followed by another successful performance led by Hermann Levi in Munich.

He is now acknowledged to be one of the greatest symphonists of the Romantic era. His influence on Mahler, Richard Strauss, Schoenberg, Sibelius and Hugo Wolf is beyond doubt. He still has detractors who find his expansive, mystical and unconventional works awkward, massive, repetitive and boring. However, over the last 150 years, Bruckner has found a growing number of devotees within the professional music community, and his symphonic and choral works have never been more widely heard than they are today in concert halls and online.

This year marks the bicentenary

of Bruckner’s birth and four Australian orchestras will perform three of the Austrian master’s most sublime symphonies.

This month, on top of QSO’s Ninth Symphony, Simone Young will bring her extensive knowledge of Bruckner to bear on his Symphony No. 8 with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, where she is Chief Conductor. The enduringly popular Romantic Symphony No. 4 will be performed by the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra under Daniel Carter in September and the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra under Chief Conductor Eivind Aadland in November.

Anton Bruckner was born on 4 September, 1824, in Ansfelden, not far from Linz in Upper Austria. His father Anton Sr. was the village schoolmaster and organist and his mother sang in the church choir. The couple had 11 children, only three of whom survived to adulthood. Bruckner was taught to play the organ by his father and started deputising for him when he was 10.

The following year, he was sent to his cousin Johann Baptist Weiß, a very competent composer, to further his musical abilities. After his father’s death, Bruckner enrolled as a chorister at the nearby St Florian monastery, at the age of 13. The Abbey basilica’s Baroque interior is awe-inspiring, and Bruckner was immediately bowled over by the sound of the great organ.

St Florian gave him a rigorous Catholic and musical education, but instead of a career in music, he opted to follow in his father’s footsteps and qualified with very high marks as a teacher. He worked in a couple of small village schools but he was not keen on having to mow the lawn and shovel snow in addition to teaching. When the assistant teacher post at St Florian became available, he was still only 21 and jumped at the opportunity. He spent hundreds of hours in the monastery’s splendid library with its extensive collection of musical scores. Eventually, he became St Florian’s principal organist.

Bruckner was an eternal student and while teaching at St Florian, he also studied contrapuntal technique with a local choirmaster. During his 10-year tenure at the monastery, he produced his first notable composition, the rather Mozartian Requiem in D minor (1849), followed by the more original Missa Solemnis.

Bruckner was deeply religious and was steeped in church music from the cradle. Chorale themes are fairly common in his symphonies, as well as melodic and harmonic inflections derived from Gregorian modes. Apart from being a very Catholic region, Upper Austria is also known for its rich folk music traditions. The polka, which originated in neighbouring Bohemia, was particularly popular at the time and you can find this dance, sometimes cleverly disguised, in virtually every Bruckner symphony.

By 1855, Bruckner had found his (musical) feet and gave up teaching to become the cathedral organist in Linz, but he still lacked the confidence to compose symphonies. He took a six-year correspondence course in harmony and counterpoint with the eminent Vienna-based professor Simon Sechter, who demanded that he refrain from composing while studying with him.

Once a year, Bruckner travelled to Vienna to take the tough exams. For his final test at the Vienna Conservatory, he had to improvise on an organ fugue. He executed the task so brilliantly that one examiner, the influential conductor Johann von Herbeck, burst out in admiration, “He should have examined us! If I knew one tenth of what he knows, I’d be happy.”

By the time Bruckner had reached his 40s, he was feted all over his homeland for his exceptional ability to improvise on the organ for hours. He was invited to play in Paris and gave sold-out recitals in London at Crystal Palace and the Royal Albert Hall. Though insecure about his symphonic skills, he unashamedly blew his own trumpet about his improvisational skills and even called himself “Austria’s best organist”.

Bruckner now had a firm grounding in music theory, but Sechter had not taught him symphonic composition. He needed a more practical approach and the cellist and opera conductor Otto Kitzler, who was nine years his junior, managed to ignite the spark. Apart from schooling him in orchestration, Kitzler introduced him to the world of Richard Wagner. Kitzler organised a production of Tannhäuser and at the same time studied the score with

Bruckner. The impact could not have been more direct and transformative.

In 1865, Bruckner was invited by Wagner, whom he referred to as ‘der Meister’, to attend the Munich premiere of Tristan und Isolde. It made an indelible impression on him. Three years later, he returned to Munich to see Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg and had a more in-depth talk with his idol. At their third meeting in Bayreuth, fuelled by great quantities of beer, Bruckner asked Wagner to be the dedicatee of either his Second or Third Symphony.

Wagner looked at the scores and picked one, but the next day Bruckner had forgotten which one he had chosen. He wrote to Wagner asking if he could remind him. “Symphony in D minor, where the trumpet begins the theme?” “Yes! Best wishes!” came the brief reply.

Bruckner’s music is often called ‘Wagnerian’ because of its orchestral sonority, expanded timeframes and chromatic harmonies. But listen closely and it becomes clear that he rarely sounds like Wagner.

German conductor Markus Poschner has recorded all 19 different versions of Bruckner’s 11 symphonies with his Bruckner Orchestra Linz and the ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra. Poschner thinks that too many conductors press the ‘Wagner button’ when interpreting Bruckner.

“Of course there’s a big influence of Wagner, but he always used the Schubert orchestra. There is no piccolo flute, no bass clarinet, no English horn. In the late symphonies, we hear Wagner tubas and even harps. But that is the only approach to the world of Wagner. Schubert remained Bruckner’s musical touchstone,” says Poschner.Bruckner took his veneration to an extreme by attending the exhumation of both Schubert and Beethoven when their bodies were moved from Vienna’s Währing cemetery to the Zentralfriedhof.

Upon hearing of Wagner’s death, Bruckner turned the Adagio of his Seventh Symphony, which he was composing at the time, into a mournful tribute. Unfortunately for Bruckner, the country’s most powerful critic, Eduard Hanslick, was a staunch critic of Wagner’s Romantic emotionalism and the views he set out in the essay Music of the Future. Hanslick (like many other Viennese critics) was a supporter of Brahms’ conservative composing practices and antiquarian tastes. Bruckner was labelled a Wagnerian and became a hapless victim of Hanslick’s sharp pen.

Nonetheless, Wagner’s rule-breaking ideas and Kitzler’s lessons triggered Bruckner’s creativity and set him on a path toward his own individual style. Over a period of six years, from 1862 to 1868, his compositional output grew exponentially. Of particular note are his three Mass settings.

His Symphony in F minor, written in 1863, showed great promise. The Symphony No. 1 from 1865 – nicknamed “Das kecke Beserl ” (The Saucy Maid) by the composer – clearly owes much to Schubert’s Symphony No. 9, The Great, while throwing in references to Tannhäuser for good measure. But the heavy workload made Bruckner restless, causing his OCD to flare up, resulting in a mental breakdown. During the summer of 1867, he underwent cold-water treatments at the sanatorium in Bad Kreuzen. He recovered fairly quickly, but it was time for a change of scenery and a stab at greatness.

After much persuasion from Johann von Herbeck, his champion at the Conservatory exam, Bruckner accepted the professorship at the Vienna Conservatory, which had become available after Simon Sechter’s death. Thanks to Herbeck’s considerable influence, he was also made provisional organist at the Imperial Court Chapel.

A few years later, despite Hanslick’s protests, Bruckner became a lecturer in harmony and counterpoint at the University of Vienna. His teaching methods were effective, but slightly unorthodox, and it was not uncommon for him to suddenly interrupt a lecture to say a prayer. Students who visited him at home were disturbed by a photograph above the piano showing his mother on her deathbed, while another student complained that he’d addressed her as “darling”. (He was exonerated but refrained from teaching young women thereafter.)

Nonetheless, he was liked by most pupils, many of whom went on to have successful conducting careers.

Although never formally Bruckner’s pupil, Gustav Mahler also attended some of his lectures and championed his symphonies as a conductor, controversially editing some of them so they’d appeal to a wider audience.

Bruckner complained that he never found enough time to compose in Vienna, but over the summer holidays he would take a spiritual retreat and devote himself to composing. He had his own cell at the monastery of St Florian (which you can still visit). Another favourite refuge was nearby Steyr, an idyllic town where Schubert composed his Trout Quintet.

Between 1871 and 1876 Bruckner wrote four largescale symphonies. His Symphony No. 2 was initially rejected by the Vienna Philharmonic, but with the help of some wealthy patrons, it was premiered at the Vienna World’s Fair in 1873 with the composer on the rostrum.

It was well received by the audience, but the critics were divided. That same year, the first version of his Symphony No. 3 was completed on 31 December, but there were to be three more revisions. After a test rehearsal, the Vienna Philharmonic musicians turned down the original version. Johann von Herbeck promised to conduct the second version in 1877, but he died and Bruckner had to replace him. During the performance, some of the Vienna Philharmonic musicians started laughing and walked off. The fiasco was complete when most of the public left. On top of that, Eduard Hanslick wrote a scathing review. Bruckner, of course, felt humiliated by the failure, but it didn’t slow him down. He may have lacked self-assurance, but his resilience was remarkable.

He began writing the programmatic Fourth Symphony, which he subtitled Romantic, only days after finishing his Third. He reworked it between 1878 and 1880 but remained unsatisfied after the 1881 premiere, and made some final adjustments in 1888.

Currently based in Germany, Australian conductor Daniel Carter will conduct Bruckner’s Fourth for the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra in September. He was Simone Young’s assistant when she recorded a complete cycle of first versions of Bruckner symphonies with the Hamburg Philharmonic State Orchestra. Carter will conduct the second of the three versions, which has the popular ‘horn call’ Scherzo. He says that having poured over all the different versions and listened to many recordings, he started noticing that over the years many small changes had crept into interpretations.

“With Bruckner, it’s maybe because conductors have the feeling that he himself was so uncertain and he needs a bit of help,” suggests Carter, who went from not really understanding Bruckner to connecting with his “amazingly grandiose music” during his time assisting Young.

While studying the third version of the Fourth Symphony, he discovered that Bruckner had added quite a few tempo markings and comments that are intended for the conductor – some of which are quite surprising. “When you compare the critical edition of the second and third version, in the third version there are lots of tiny little markings of “hold back”, “going forward”, and they almost exclusively stand at points where you would not at all expect it. I found that fascinating – to see a phrase where every time you have ever heard it [performed], it gets slightly faster, and to then see what [Bruckner] has written after the experience of watching people conduct it – “zurückhaltend ”, hold it back. That must come out of some experience where he has heard it, but not how he wanted it to be,” says Carter. “I copied all Bruckner’s markings out of my score of the third version into the second version. And I really try to hold myself to them. But it’s really hard!”

“One of the most fascinating things when you spend time with Bruckner is just how much doesn’t make sense. It’s a joy almost, in a really weird way, to sit there and take these different traits and try and put them together. It’s like you’ve been given puzzle pieces that can never quite properly go together,” concludes Carter.

Well-meaning friends and conductors pleaded with Bruckner to compose more polished and conventional symphonies. He was advised to smooth out dissonances, to cut the sudden pauses and the long finales, and not to divide his orchestral colours into blocks. We know that he only reluctantly accepted many of the suggested changes.

A number of his students helped with the revisions and reorchestrations, but despite their good intentions, they would occasionally add their own alterations to a score behind the composer’s back. It’s been incredibly hard for musicologists working on the latest edition of the symphonies to find and root out those additions.

How is one to determine which version of a Bruckner symphony best represents his intentions?

This is called ‘The Bruckner Problem’. A few years before he died, Bruckner bundled up the 19 versions of the 11 symphonies he approved of and stipulated in his will that the manuscripts were to be sent to (what is today) the Austrian National Library.

The Seventh Symphony was hailed as a masterpiece and became Bruckner’s international breakthrough, but he asked Hans Richter not to perform the work in Vienna because he feared Hanslick’s and the local critics’ vituperative remarks. Bruckner’s protest notwithstanding, Richter went ahead in March 1886 and the concert was a huge success. Bruckner, the symphonist, had finally conquered the imperial city’s audience and critics.

However, when Bruckner asked Hermann Levi to premiere his Eighth Symphony in Munich, the German conductor declined (in the most gentlemanly fashion).

Levi was an ally, but he couldn’t get his head around the Eighth. Bruckner was deeply hurt, but nevertheless he started reworking the score and completed a much shorter version three years later. Two more years passed and, in 1892, the less edgy second version was premiered by the Vienna Philharmonic under Hans Richter. The reception was mixed, but his fame was now spreading beyond German-speaking countries. His legacy as a major symphonic composer was secured.

Bruckner worked on the Ninth Symphony intermittently from 1887 until his death nine years later. He was distracted by the never-ending work with various revisions and increasingly interrupted by illnesses that meant he had to give up teaching.

He intended his Ninth – like Beethoven’s Ninth on which he had modelled so many of his own symphonies – to be his summum opus (greatest work). He dedicated it to “dem lieben Gott” (his beloved God). It is tempting to interpret the symphony as a tortuous, at times brutal, but honest self-confession with religious overtones.

The pounding Scherzo could be interpreted as a danse macabre. Perhaps the Adagio gives us the resurrection and a glimpse of paradise. Bruckner certainly never found himself “nearer, My God, to Thee” than in his Ninth Symphony.

He intended to add a final movement to what is his most radical symphony. But even in its uncompleted form, it could be considered a structural bridge between Romanticism and modernity.

“I’m a bit of a romantic soul. We like unfinished pieces, because there are so many question marks at the end,” says Johannes Fritzsch. “It is still a complete piece for me.”

Bruckner died in 1896. The St Florian monastery, where he had spent some of his happiest times, was honoured that he chose to be buried in the abbey’s crypt. In accordance with the directions in his will, his sarcophagus was placed directly beneath the grand organ which he had practically made his own. There he lies in his bronze coffin, sharing the sepulchral chamber with some 6,000 Christians who served in the monastery and whose skulls and bones have been stacked visibly and very neatly in the vaulted wall. A more appropriate final resting place for Anton Bruckner, one of the greatest symphonists, would be hard to find.